What happened after the forced repatriations?

The men – union activists from Liverpool

We know that Shanghai men were held in Hong Kong at the beginning of 1946 because so few ships were proceeding beyond Hong Kong. Shanghai men were also being held in Singapore because of shortage of food and accommodation and a similar shortage of ships going on to Shanghai. Some men jumped ship in each of these ports and are likely to have remained there.

Soon the Kuomintang backed but apparently Communist infiltrated Chinese Seamen’s Union had transferred lock, stock and barrel to Hong Kong. Interestingly, officials of the Union surface in 1947 in Hong Kong as representatives of the Hong Kong Seamen’s Union. A painted sign on the side of building in Jordan Road, Hong Kong still continues to show where they were based.

Given the Kuomintang mass executions of unionists from the 1930s onwards such an exodus is not surprising. Certainly, any men in the Liverpool Chinese Seamen’s Union, the Communist Organisation, would have been in danger in Shanghai at this time. The end of the war with Japan seems to have been the cue for an upsurge of repression. Workers who were politically active simply disappeared.

Nor would those who were union activists amongst the men forced to leave the UK have been safe in Communist China. In 1951 union members from Hong Kong travelling into China were detained and one Hong Kong union official was executed there.

Malaysia and later Singapore when it separated from Malaya would have been equally dangerous. The struggle with the Communists, who were mainly ethnic Chinese, would have made life for any of those with Communist affiliations dangerous indeed.

It seems that only Hong Kong was likely to provide a safe haven for any of the union men.

The men – the search for better pay

At the end of 1947 Shanghai men were flocking to the China Merchants shipping company on account of the apparent high rates of pay. This despite Holts having to increase pay by 50% earlier that year so uncompetitive had their rates become in that period of hyper-inflation.

This fits to some extent with verbal evidence we have that Shanghai men signed for such Shanghai lines as YK Pao and HH Tung and moved to Hong Kong with these shipping magnates between 1946 and 1949.

High unemployment amongst seamen in Hong Kong in 1948 would surely have meant that men who had jobs with Shanghai lines would have remained with them.

Coupled with what we know of the situation for those with union connections, it seems possible that a number of the men ended up in Hong Kong.

Did some of our fathers end up in Hong Kong? We know that many people from Shanghai did flee there when the city fell to the Communists in 1949. One whole district of Hong Kong Island known as North Point became a little Shanghai.

The women and we their children

In August 1946 an article appeared in the “News Chronicle” newspaper that a Mrs. Lee was protesting that 150 women married to Chinese men had been left destitute. The article said that each of the women had an average of three children giving a possible total of around 450 in all.

An article in the Liverpool paper the ‘Echo’ of 19th August 1946 quotes figures that are approximately twice those in the ‘News Chronicle’. This article says that that there were 300 women. It reports that some of these women had six or seven children. This shows how long term some of those relationships had been before the men were forced out.

We were the children. But how many of us are there? Perhaps between 450 and 1000. We just do not know the real numbers.

Despite hunting through the newspapers of the time, we have not been able to find any further reference to the women. But we do have the stories of some of them from their children.

Our mothers believed they had been deserted. At least one of them tried to commit suicide.

Some did receive word from their husbands and partners. Letters arrived from Hong Kong or Taiwan and other parts of the world. There had been trouble on board ship. They would write again. How were the children?

Sometimes presents arrived for the children. But gradually the letters ceased, the parcels stopped. Perhaps the letters stopped because our mothers did not reply.

Letters were intercepted by relatives and not passed on to our mothers. Some of our mothers had changed address and perhaps the letters did not get to them. In other cases, our mothers had no addresses to which to reply to their men.

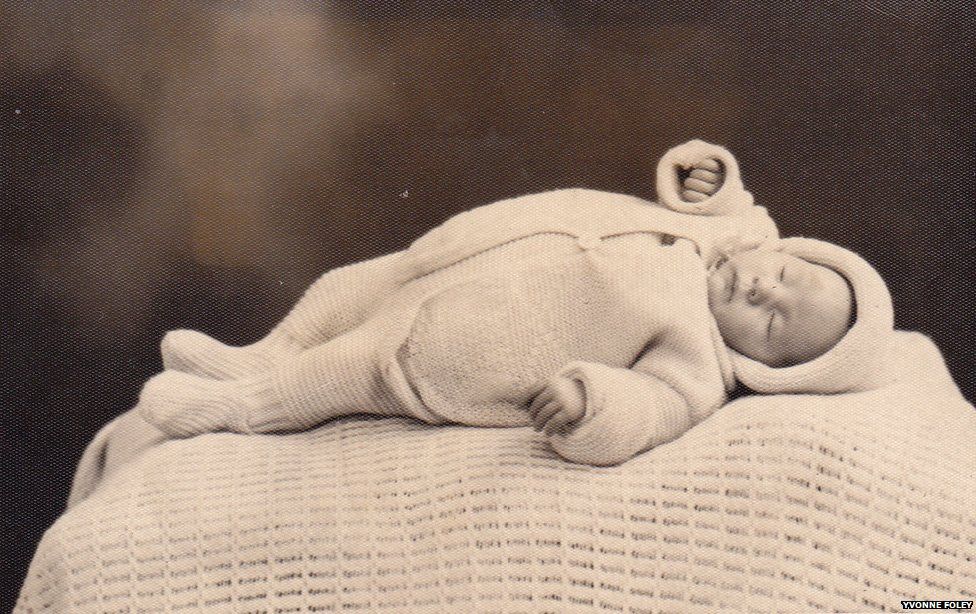

As time went on some of the women had their children placed in children’s homes. There they remained for many years. Others had their children adopted. Some of us went to white couples. Some went to mixed race couples – Chinese men and their Liverpool wives. For in the chaos of the forced repatriations, some men had been able to remain.

Many of the women kept their children. Some struggled at two or more lowly paid jobs in an effort to provide for their children.

Some of the women remarried but most seem to have had hard lives. They lived in poverty and in many cases they died young.

We believe that certain of the men did get back – but too late. It seems that around the period 1950/1 some men started to re-appear. Where these the men who had joined Shanghai shipping companies and who now lived in Hong Kong? Was it at this time that these companies started to send their ships to the UK?

Some of us who lived in Liverpool have recollections of Chinese men appearing in our lives. Talking to our mothers. Asking about our mothers. Stopping us in the streets to ask about us and about our mothers.

We have memories of arguments between our mothers and our step-fathers. Separations between our mothers and our step-fathers. Mothers who take us to Chinatown, who meet Chinese men there and who leave there in tears.

But what of us?

Few of us had any connection with the Chinese/Eurasian community. We lived close to each other in Liverpool but few of us ever met.

Some of us did not know we had any Chinese blood until we were teenagers or even adults. We knew we looked different to others around us but we never knew why.

In a few cases our mothers resented us. We reminded them of a sad time in their lives. We were the children they did not want. Moreover, we were not the children of our mothers’ new husbands. For those men we were reminders of our mothers’ previous lives.

For others of us the situation was different. We too grew up in poverty. But our fathers treated us as their own children. We were fortunate.

A surprising proportion of us have worked in the caring professions. Nurses and counsellors. Most of us have striven to further our educations. Most of us live in some degree of material comfort. Generally, we have been ‘successful’.

Many of us still live in Liverpool or in the North West of England. Others have moved out of Britain and live in Australia and Canada. Some of us have visited China but most, it seems, have not. We are British. We are Liverpudlians. We are no different in that to all the Liverpudlian Eurasians who came before us.